I thought I’d better check this third plate, which is another date, see if there’s an image there in the right place that would be consistent with the images on the other plates. That was the final proof.” – Clyde Tombaugh

Pluto was discovered on 18 February 1930 by young astronomer Clyde Tombaugh. His technique was humble, switching mechanically between photographic plates to see if one of the faint points of light appeared to move. On that day, he noticed a moving object on photographic plates taken on 23 and 29 January of that year. After the Lowell observatory had taken confirmatory photographs, news of the discovery was announced on 13 March 1930.

The naming process would prove complex, and human. Candidate names include Zeus, Percival and Chronos. The final choice of Pluto was proposed by Venetia Burney, an eleven-year-old schoolgirl from England, who was interested in mythology. She would earn £5 for her idea. The name would inspire Walt Disney in naming his cartoon dog, and the discoverer of the radioactive element plutonium.

Within months of discovery, Pluto was appearing in fiction, including the Cthulhu Mythos stories by HP Lovecraft. But the main role of Pluto in popular culture was to be a symbol of vast distance, cold loneliness and the unknowable. Even the mighty Hubble telescope would find only the barest hints of what lay on its surface, a surface that would sometimes reach temperatures as low as 33 Kelvin, within touching distance of absolute zero.

Eventually that would change.

Indeed, a Pluto flyby was a possibility for the “Grand Tour” undertaken by Voyager 1, and would have happened in the late 1980s. However, a close approach to Saturn’s moon Titan was selected instead, since it was seen as of much greater significance than tiny, remote Pluto. As a consequence of that, when Voyager 2 encountered Uranus and Neptune, Pluto became the only traditional planet whose face was unmapped and unknown.

So, in 1989, a group of scientists formed the “Pluto Underground” to promote the idea of a mission. At the heart of this alliance was a scientist called Alan Stern, who would pursue the concept of a Pluto mission with intense passion and would eventually become the Principle Investigator for New Horizons.

It wasn’t an easy process. Initial ideas were rejected, sometimes with great controversy. Then a competition was held, in which NASA would select a mission concept to fund as part of the first mission of the mid-cost New Frontiers program. New Horizons won, was rejected but then re-selected, for a mission cost of around $700m.

The probe finally lifted off from Pad 41 at Cape Canaveral at 14:00 on January 19, 2006.

The triangular New Horizons spacecraft has been compared in size and shaped to a grand piano. Unlike a piano, it is powered by a plutonium battery – more formally called a radioisotope thermoelectric generator or RTG. There’s irony here. The first probe to Pluto is powered by an element named after it.

New Horizons was the fastest spacecraft ever to leave Earth, it was accelerated even further after a scientifically valuable flyby of the Jovian system.

Almost a full decade after lift off, New Horizons reached its destination – the distant ice world of Pluto, almost exactly on the day that marked the 50th anniversary of interplanetary exploration. Because New Horizons is 4 ½ light hours away, the extraordinarily fast encounter was dark to the ground, powered by software and supported by immense pre-planning.

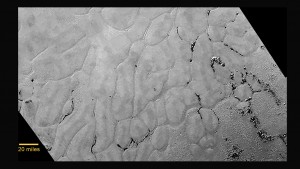

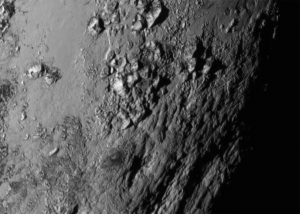

But shortly afterwards, and for first time in many years, we had the raw pleasure of seeing – as a connected human community – the faces of strange new worlds. We saw the cratered surface of Charon, the major moon of Pluto, cracked by a mighty canyon and marked by a mountain seemingly buried in the heart of a crater, like a giant Norman castle. On Pluto we saw a landscape of the Norgay Montes ice-mountains adjacent to a vast young plain (Sputnik Planum) fractured into polygon shapes – a landscape that is somehow active and renews itself at those temperatures of 33 kelvin.

The triumph of New Horizons completes a story that combines the initial discovery of a very distant world, the vision of those that pursued a Pluto Mission for decades, and the gigantic contribution NASA and the US have made to this period of exploration. That story also includes the remarkable efforts of the New Horizon team, across complex planning, the spacecraft design, the construction of the science instruments and the management of mission operators.

It is of course a human story, not just a tale of achievement in technology and engineering. The probe itself carries a number of artifacts that tie it back to the beginnings of the Pluto story. Two stand out for me.

The Venetia Burney Student Dust Counter or VBSDC was built and is operated by students at University of Colorado. It measures the dust peppering New Horizons during its voyage. It is named after the little girl who named the distant world in the early 1930s.

And most moving of all is the fact that the craft contains one ounce of the ashes of Clyde Tombaugh himself, the young man who discovered Pluto and who would never know that his remains would pass close to 10,000 kilometers about the surface of the planet he was the first to glimpse.

As principal investigator and life-long Pluto advocate Alan Stern has said: “We have completed the initial reconnaissance of the solar system.” And like all such missions, for a moment it connected us all, as an example of the best we can do.

KEITH HAVILAND

Keith Haviland is a film producer and founder of Haviland Digital Limited – dedicated to intelligent content across film, TV and other media. He is one of the producers of the award-winning Last Man on the Moon. He has been a business and technology leader, with a special focus on how to combine big vision and practical execution at the very largest scale, and how new technologies will reshape all that we do. He is a Former Partner and Global Senior Managing Director at Accenture, and founder of Accenture’s Global Delivery Network.